A raggedy used copy of the book by Claude Bernard which I ordered online. It has been highly recommended to me by some of my colleagues. Now to find the time to read it hmmm …

Christmas markets in Berlin

Eponymously named diseases are a slippery slope

OK so I admit the following post is a bit of a random rant.

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, but it has always been my favorite example of an eponymously named medical disease. It’s so much more fun than saying ‘Müllerian agenesis’. So I did some reading on the condition and one thing led to another (so I’m taking you through my train of thought here, bear with me) Interestingly, the alternative name of the condition is also an eponymous term – named after Johannes Peter Müller, the German physiologist who described the ducts that develop into the female reproductive system in early development. He worked at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (the medical school of the HU is the Charité, where I am now studying). While there, he tutored both the prominent physician/physicist (!) Hermann von Helmholtz and the ‘father of pathology’ Rudolf Virchow. The latter is buried in St. Matthews Cemetery in the locality of Schöneberg, a few blocks away from my flat in Berlin (also, Albert Einstein lived in this same locality for 15 years). Now back to MRKH syndrome – one of the people who described this condition is Baron Carl von Rokitansky, a pathologist and physician who worked with Johann Wagner, a relatively less known pathologist (perhaps due to his death at 33 years of age). Together they performed the post-mortem examination of Ludwig van Beethoven – this was Rokitansky’s first of over 50,000 autopsies in his career.

And that’s how I spent my ‘precious’ free time.

Found some inspiration …

From the Roman poet Virgil:

Miseris succurrere disco. (I learn to relieve the suffering)

Now if that’s not pure inspiration for an overloaded student I don’t know what is!

A very brief summary of the past few weeks

Symposia, like hard liquor, should be taken in

reasonable measure, at appropriate intervals.

Perspectives in Biology and Medicine

Sir Francis Martin Rouse Walshe

(British neurologist)

The past few weeks for me have consisted of classes in ridiculously high measure and lacking sufficient intervals. But fear not, I shall be blogging again soon!

My Magna Carta

Today was one of those days where I had the entire afternoon free (days like this have become exceedingly rare for the last couple of months). Instead of spending the lovely (and by lovely I mean gray and drizzly) day taking a stroll outdoors or going for a jog like a true Berliner, I stayed home. Specifically, I stayed in bed and dug my claws into something I have been wanting to read for a long time now – Sir Charles Bell’s Idea of A New Anatomy of the Brain. The surgeon, who was educated at the University of Edinburgh, was one of the first people to link the anatomy of the brain and nerves with clinical practice, and describe the relevance of the former in health and disease.

Often referred to as the ‘Magna Carta of Neurology’, the essay is an outstanding description of the human brain. Not only did it challenge the prevailing view of the structure and function of the brain and nerves back then, it did so with sheer poetic elegance. In the essay he hypothesizes how specific stimuli acting on nerves or sensory organs are not what cause us to perceive sensations, but that the brain is the organ responsible for perception. He gives examples to support his argument of everything from phantom limb to ‘seeing colors’ when the eye is hit by a mechanical force. His conclusion that “The operations of the mind are confined not by the limited nature of things created, but by the limited number of our organs of sense.” is considered revolutionary for the time, when people thought of the brain merely as a ‘relay station’ which receives sensation and sends motor commands.

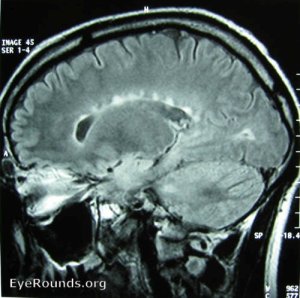

Another interesting theory which he makes based on experimental evidence is that the surface of the brain (the gray matter, which contains cell bodies of neurons) when damaged has far more obvious effects on the afflicted than when the white matter is damaged. We now know that the relative resiliency of white matter fibers causes this (for example, alternative pathways to bypass the damage can be made) – and further proof of this is the fact that demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis are often associated with white matter damage without ‘obvious’ external manifestations.

His statements about the structure of the human body are nothing short of inspirational (particularly to a physician/scientist) – he says (about the eye) “… a system beyond our imperfect comprehension, formed as it should seem at once in wisdom; not pieced together like the work of human ingenuity.” This immediately brought to mind one of my favorite quotes about the brain from Emerson Pugh – “If the human brain were so simple that we could understand it, we would be so simple that we couldn’t.”

Of course, not everything that he postulated in the essay was found to be scientifically accurate. One example is his theory of the origins of the two roots of spinal nerves from the cerebrum and cerebellum separately – although he is the first person to have described the distinction between sensory and motor nerves, and hypothesize that there are corresponding areas inside the brain. It is my opinion that the broad concepts which he puts forward in this essay, not the small details, are what makes it a true gem of scientific literature.

Some entities which are named after him include:

Bell’s palsy – idiopathic unilateral palsy of the facial nerve

Bell’s phenomenon – a clinical sign in which a person affected with Bell’s palsy tries to close his/her (affected) eye and the eye rolls upwards

Bell’s (long thoracic) nerve – supplies serratus anterior, a chest wall muscle

Bell’s law – states that posterior roots of spinal nerves contain sensory fibers and anterior roots contain motor fibers

(on the prevailing theories regarding the brain):

“Thus it is, that he who knows the parts the best, is most in a maze, and he who knows least of anatomy, sees least inconsistency in the commonly received opinion”

Sir Charles Bell

MRI of a patient with multiple sclerosis showing periventricular white matter lesions in the corpus callosum. Despite their size, such lesions are often asymptomatic and may be discovered incidentally.

From: EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology, University of Iowa

Note: The above depicted pattern of white matter lesions was first described by another alumnus of the University of Edinburgh – James Walker Dawson (hence the name ‘Dawson’s fingers’).

The prescription conundrum

This week as part of my studies at Edinburgh we touched on the issue of drug prescribing. Prescribing is considered by many to be the role that epitomizes the medical profession. It’s a tool which is in some way unique to doctors (at least in terms of the extent to which they utilize it) and is the major way by which we apply our knowledge and skills to care for patients. Prescribing medication is far more than just writing words on a piece of paper – it is a dynamic and multi-layered process by which the physician identifies and details the approach to management, conveys this message to the patient, gains feedback and ‘tweaks’ the treatment for optimum results.

One thing about prescribing is that, despite its complexity, the lower you go on the medical ‘hierarchy’ so to speak, the more prescriptions you find. Junior doctors do the most prescribing – simply because they are often the ones who have the most contact with patients. Despite this, many junior doctors do not feel they are equipped with enough knowledge, skill or experience to effectively (or even safely) prescribe after graduating medical school. I certainly thought so.

Two semesters of pharmacology (the study of the actions of drugs) and one of therapeutics (the application of pharmacology in the use of medicines to treat disease) left me with a decent knowledge of the way drugs interact with the body (and vice versa), and of which medicine to use in which situation. But about prescription writing? Nothing. I scribbled my first prescription as a junior house officer in my pediatrics rotation – I can’t remember exactly what it said but I can imagine it contained about as much meaningful medical information as my left big toe. Thankfully the medication was to be dispensed from the internal pharmacy at the hospital where I worked, and the pharmacist was nice enough to make a few comments about my prescription writing technique.

Now, the thing is that this seems to be a universal problem among junior doctors – there simply isn’t any opportunity to practice prescription writing in a real-life setting during medical school. The result is that a lot of mistakes are made – meaning unnecessary drugs are prescribed, avoidable side effects are observed, costs of treatment increase and medico-legal issues arise. But it’s not fair to pin the blame solely on junior doctors – both from my experience and from several formal studies conducted, senior doctors also make a fair amount of prescribing mistakes, and many do not implement an optimum prescribing technique. Moreover junior doctors tend to have a more solid knowledge of the more basic aspects of drug action and interaction than their senior counterparts – the ‘is vancomycin an aminoglycoside?’ debate I once had with one of my senior colleagues lingers in my memory (Sometimes I wonder if I should avoided the topic altogether and better utilized that hour of my life, but the distinction isn’t exactly arbitrary, aminoglycosides’ use is mainly limited to gram-negative bacteria while vancomycin has a much broader spectrum, but I digress …).

So a year later after completing my internship I’m slightly better at prescribing – I’ve learned to dot the i’s and cross the t’s, but the need to reform this aspect of medical education is undeniable.

More on prescribing soon!

A little taste of Edinburgh in Berlin (from a Neuroscience point of view)

Today, my two academic sanctums met in the form of a lecture on cerebellar neuronal circuitry. The lecture which took place at the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (where I am currently doing an MSc in Medical Neuroscience), mentioned the work of Professor Richard Morris of the Centre for Cognitive and Neural Systems at the University of Edinburgh. Prof. Morris developed criteria in 2000 for the hypothesis that synaptic plasticity (i.e changes in connections between neurons) is responsible for formation of memories. A detailed review of his work is referenced below.

Martin, S.J., P.D. Grimwood, and R.G.M. Morris, Synaptic Plasticity and Memory: An Evaluation of the Hypothesis. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 2000. 23(1): p. 649-711.

My posts have been few and far between recently – I am neck-deep in assessments, seminars, journal clubs, lectures, reviews etc. However, there will hopefully be more to come on synaptic plasticity and memory, as well as more general updates this weekend!

Head-first into the research abyss

The beginning of October officially marked the start of my career as a scientific author. The project was a small epidemiological study I conducted in my second year of medical school in collaboration with a colleague of mine and a visiting physiology professor. The survey took months of hard work, including hours of data collection from random subjects around the streets of Khartoum. This was before I had received any formal education in research methodology (although I had taken a course in Biostatistics), and I have learned a lot since then. The process of publication itself turned out to be an even more lengthy and tedious task than the data collection, analysis and writing up of the article – which I had not expected (this being my first experience with scientific journals). I finally breathed a sigh of relief a couple of weeks ago when I saw the article in print. Below is a link to the full-text version of the paper.

http://www.jpma.org.pk/full_article_text.php?article_id=3712

Inspiration at Edinburgh

Despite having only been a student at the University of Edinburgh for five weeks, it’s not hard to see why its style of education has created so many visionaries and pioneers in the past. Just last week I read a paper provided as part of my statistics course – it claimed that the majority of scientific research findings are false. Well, it actually did more than that. Being a scientific paper itself, it actually proved that most findings are false. And I’m talking proved in the ways that medical people rarely understand – mathematics-ey ways! The first thing that crossed my mind was, this guy (the author) must be some untrustworthy/unknown person trying to make a name for himself by claiming something radical, and attempting to prove it with some complex mathematics which he knows us poor math-illiterate medical folk would never comprehend. It turns out, the author is one of the most respected authorities on the subject in the world, and the maths make sense (I know, because after trying to wrap my head around the first equation, I gave up and asked a statistician).

So I thought – this guy made some really good points. I had been taught in medical school (in my biostatistics/research methodology courses) that the reliability of any given research result depends on p-values, sample sizes, the presence of bias, etc – and that if all these are ‘good enough’, I can assume that the finding itself is correct. But I wasn’t so sure anymore. The paper’s conclusions surprised me, and I quite honestly didn’t know what to believe anymore! In medicine, decisions that affect a person’s health and well being (which drug to use, what test to run) depend on research results being valid. The idea that the anti-hypertensive medication I prescribed to that pleasant 65 year-old lady a few months ago may not have been a good choice is frightening. As doctors, we rely on evidence-based decisions every day – it’s what we fall back on. The days of ‘I chose drug A because I read it in a book/so-and-so told me it’s the right choice’ have passed, long before I could even say the word ‘anti-hypertensive’ in fact. Then came the days of ‘I chose drug A because this study proved it to be better than drug B’. Now it seems that this phase in medical practice may soon be drawing to an end as well, at least if we don’t change the way that we interpret research.

After the initial shock subsided, it dawned on me that this was a good thing – it’s important to know that what we think works may not work as well as we think it does! It gets you thinking of ways to improve – whether it’s being more critical when reading a scientific paper or trying to develop more reliable statistical methods for future use. I now realize that only a truly inspirational academic institution like the University of Edinburgh can get someone like me, so fixed in the ways that were hammered into him during medical school, to challenge the status quo and think outside the box.