Neurology. An infinitely fascinating yet somewhat frustrating field of medicine. People often see neurologists as doctors who spend a lot of time thinking about what could be wrong with the patient, analyzing signs and symptoms and localizing the site of disease clinically with impressive accuracy, only to have little they can actually do to treat what they’ve just discovered. Thinkers but not doers, thats the general view among other doctors as well as patients sometimes. The question is, can you blame them? As the field of medicine which I have chosen to dedicate my life to, skimming through a neurology textbook or spending the day on the neurology ward can be depressing.

Now, I’m definitely no neurology expert, but it seems there are simply no curable neurological diseases. That’s ok, an optimist may say, since curable diseases in medicine are few overall. Infectious diseases aside of course. Endocrinology, cardiology, rheumatology, whichever specialty you pick, fully curable diseases are few and far between. But how about treatment? Alleviating patient symptoms and reducing the progression of disease are certainly not the same as cures, but at least these other specialties can say they do something to help. We don’t even have that in neurology.

Perhaps it’s the general complexity of the brain, and how little we know about the way it works that contribute to the lack of effective treatments to tackle it’s diseases. It’s an attractive concept to blame this fact, however the amount of knowledge that has been gained regarding the brain over the past few decades is vast, and the resulting advances in treatments have been relatively modest. It was thought before that the central nervous system cannot regenerate, and thus what is lost is lost forever. We now know that that’s not entirely true, or at least it’s not as simple as previously thought.

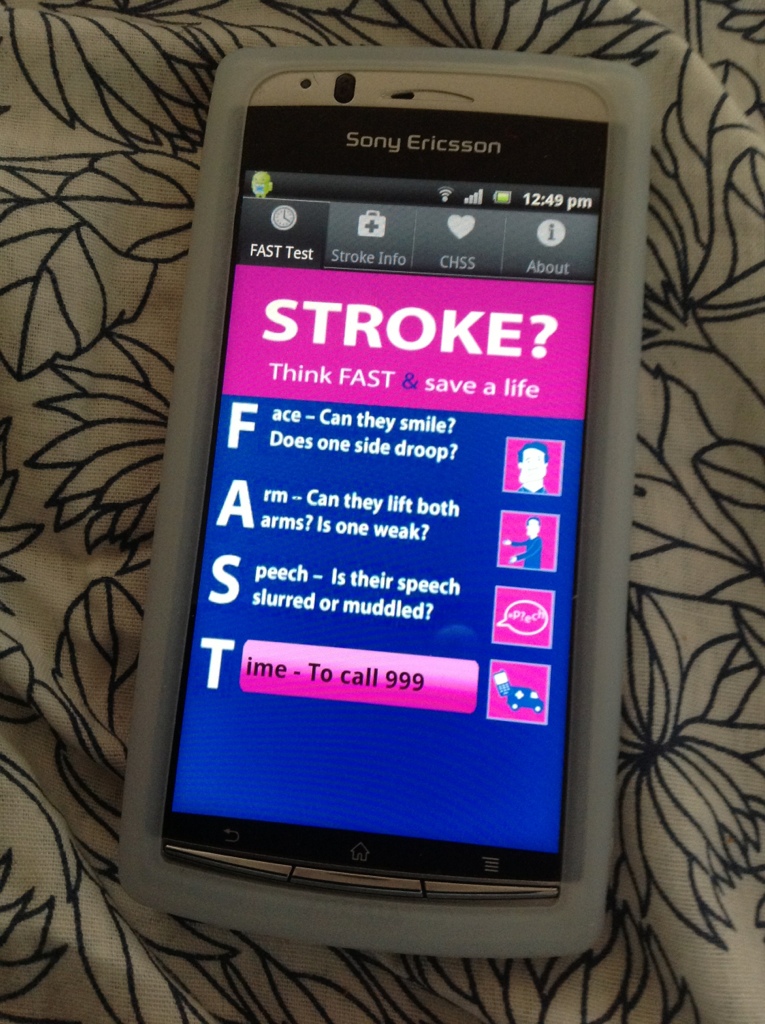

Ask a neurologist and they will say – how about stroke? Hmmm I thought so too until recently. In medical school I was taught about how thrombolysis (dissolving the blood clot which is blocking the brain vessels and essentially starving the dying brain tissue) is a revolutionary and effective treatment for stroke. Digging a little deeper it seems that’s not really the case. About 4% of people with stroke actually get thrombolytic therapy, once you sift out all the people who don’t receive it because they came to the hospital too late or because they have one or more of the many contraindications to the treatment. Four percent. The number of people you need to treat for one patient to benefit in a certain way from the treatment (calculated from early studies) seems to be around eight. Eight people for one person to benefit. Out of four percent. That’s really sad.

Please don’t get me wrong, I appreciate the efforts that were made by others for us to reach even this modest benefit from stroke treatment. It is, after all, better than nothing. But this is a recurring theme in neurology – treatments that are riddled with unwanted effects, or are simply not good enough in terms of combatting the disease. Parkinson’s disease? Drugs such as L-dopa that quickly lose their ability to improve symptoms, and eventually cause effects that can be worse than the disease itself. Multiple sclerosis? No standard therapy which reduces the number of attacks over a long period (Natalizumab is an exception, but it’s complicated – very complicated). I could go on.

Now, I’m not a neurologist and, like I said I’m therefore certainly no expert on the matter, but this is my general impression. I’m sure lots of people far more experienced than I can challenge me on these observations, but there’s no denying that neurology is far behind in treating its maladies relative to its fellow specialties. Anyway, I would hate to point out faults without talking about how we can perhaps change this in the future.

What needs to change? I’m not really sure, but it’s interesting to think about it. More research? Neuroscience can’t really claim to be a neglected field of research these days, but it had been for a long time. Maybe that’s why it’s so far behind. Do we need more research, just to make up for lost time? Perhaps the complexity of the brain in itself demands more of our attention. If that’s the answer, or part of it at least, then it seems I made the right choice by choosing to supplement my career in clinical medicine with scientific research. Do we need more neurologists or more researchers? Or do we need more neurologists who do a considerable amount of research? What can I, having chosen this career path, do to help?

It’s a cliché to say that I became a doctor to help people. I think it has even become a cliché to state that it’s a cliché. The truth is, that was a big part of my decision to enter medical school. Among other things (scientific curiosity, respectability, etc), the thought of helping people is perhaps the most rewarding and motivating aspect for everyone in the medical field. Treating patients and watching as they improve, sometimes dramatically, is something that every doctor needs in order to cope with the harsh mental and physical demands of our jobs.

The question now arises – why am I preoccupied with this? Am I losing faith in my career before it actually begins? Am I assuming prematurely that a life in neurology will be unrewarding and disheartening? I shudder at the thought of someone reading this blog years from now and using it as a reason not to give me that neurology training job (assuming that anyone at all reads it of course!). I would like to think, however, that this introspection on my behalf will make me better at my job. After all, logic dictates that the combination of curiosity and the appreciation of the faults of the status quo represents fertile ground upon which to strive for improvement. At least that’s what I hope.